Exploring the Abundance of Earth-like Planets Beyond Our Solar System

Written on

Chapter 1: The Discovery of Earth-like Planets

Recent research from UCLA indicates that planets similar to Earth could be more prevalent in the universe than previously thought. By investigating rocky debris surrounding white dwarf stars—remnants of once vibrant stars—scientists have made groundbreaking conclusions about the likelihood of Earth-like worlds orbiting other stars. Alexandra Doyle, a lead researcher at UCLA, shares insights on this significant study.

Doyle and her team employed innovative methods to analyze the chemical composition of planetary systems around distant stars. By scrutinizing the remnants of rocky planets and asteroids near white dwarf stars, they could infer the characteristics of planets that either once existed or still do in those systems. Their findings revealed that the compositions of these extraterrestrial rocks were strikingly similar to those found in our own inner solar system, particularly in their oxidation states.

“Many of the exoplanetary rocks we examined bear a resemblance to the oxidation levels found in Earth, Mars, asteroids, and chondrites [stony meteorites]. They don't resemble Mercury, which is less oxidized,” Doyle explained to The Cosmic Companion.

The team discovered that the masses of these objects also mirrored those of bodies within our solar system, often resembling asteroids or fragments of planets.

Section 1.1: Understanding White Dwarfs

White dwarf stars are the remnants of stars like our Sun, which have exhausted their hydrogen and helium reserves, collapsing into a compact form roughly the size of Earth. These stars originated similarly to our Sun, sharing comparable masses, temperatures, and surface colors.

As they deplete their hydrogen supply, energy production halts, causing the stars to shrink. This contraction allows helium to fuse into heavier elements like carbon and oxygen, generating energy once again and resulting in the star expanding into a red giant. In about five billion years, when our Sun undergoes this transformation, it may engulf Mercury and Venus, and potentially consume the lifeless remains of Earth.

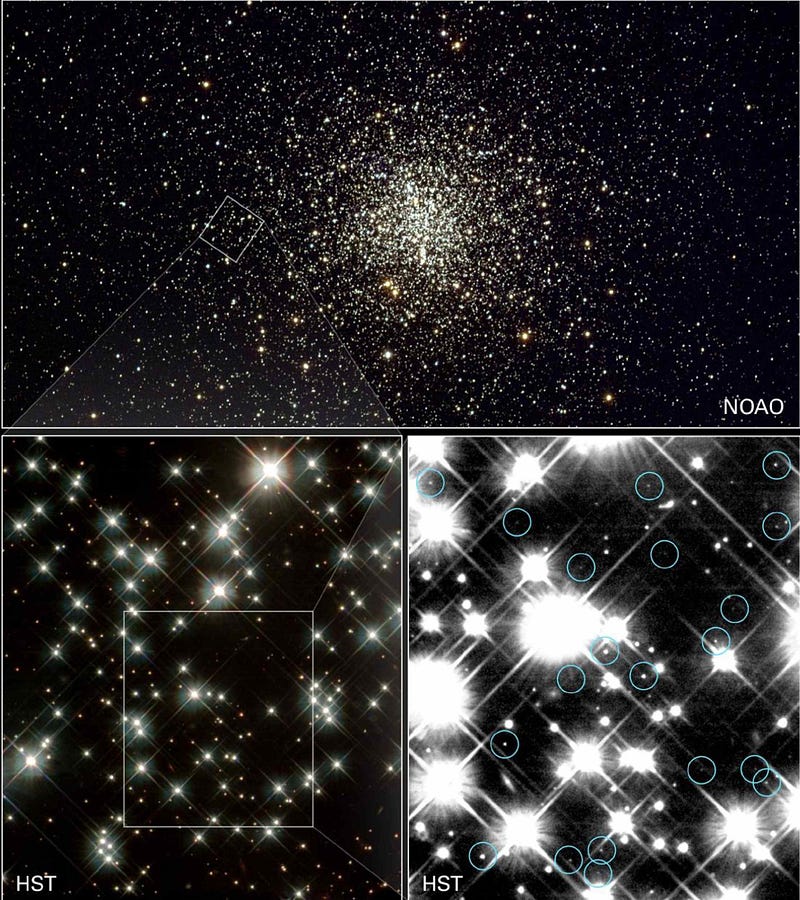

As a white dwarf shrinks, its gravitational pull draws in elements like carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen from the star’s outer layers. When studied, white dwarfs typically show only hydrogen and helium, with minimal heavier elements. Any additional elements are likely from the bodies orbiting these deceased stars.

“Determining the composition of planets outside our solar system is challenging. We utilized a pioneering method to analyze the geochemistry of extraterrestrial rocks,” remarked Hilke Schlichting, a co-author and associate professor at UCLA.

By examining the chemical makeup of white dwarfs, Doyle's team could gather insights into the planets and asteroids in those systems. “Studying a white dwarf is akin to conducting an autopsy on the materials it has consumed from its solar system,” Doyle noted.

Chapter 2: Insights from Debris Analysis

The first video dives into the discovery of two Earth-like planets situated in the habitable zone, which are only slightly larger than our planet. This finding sheds light on the potential abundance of similar worlds.

The analysis of data from previous astronomical surveys, including research conducted at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii, enabled researchers to decipher the composition of debris surrounding white dwarfs. Doyle's investigation uncovered silicon, magnesium, carbon, and oxygen remnants from rocky bodies, along with oxidized iron—commonly known as rust—present in the rocks colliding with the white dwarfs.

During oxidation, metals share electrons with oxygen atoms, forming a bond. Rocks from Earth and Mars exhibit a similar chemical makeup, particularly concerning oxidized iron, with Mercury being a notable exception due to its proximity to the Sun.

Until now, the extent of similarity between the chemical compositions of exoplanets and those in our solar system remained uncertain. This study suggests that the geology of many rocky planets around other stars may closely resemble that of Earth.

“The key takeaway is that these rocks share remarkable similarities with the rocky bodies found in our Solar System,” Doyle stated.

The second video discusses the surprising frequency of Earth-like planets, challenging previous assumptions about their rarity. It emphasizes the implications of this research for understanding planetary systems across the universe.

Section 2.1: Geology and Life

The geological processes and the role of oxygen have been crucial in shaping our planet and its neighbors. “All chemical processes occurring on Earth's surface can ultimately be linked to the planet's oxidation state. The presence of oceans and essential life ingredients can be traced back to this oxidation,” explained Edward Young, a UCLA professor of geochemistry and cosmochemistry.

The identification of rocky materials in alien solar systems that closely resemble our own increases the likelihood of discovering rocky planets around other stars. “We have significantly enhanced the probability that many rocky planets are similar to Earth, indicating a vast number of rocky planets exist in the universe,” Young elaborated.

Even after the Sun has faded and our solar system has transformed, the remnants of our planetary system could resemble those observed in this study. Doyle envisions a captivating scenario for the future of our solar system: “As our Sun evolves into a white dwarf, it may alter the orbits of smaller celestial bodies, such as asteroids, sending them toward the Sun. In this scenario, the white dwarf will shred these bodies, creating a debris disk reminiscent of Saturn's rings but on a smaller scale,” Doyle speculated.

This detailed analysis is documented in the journal Science.