The Remarkable Resurrection of the Aldabra Rail

Written on

Chapter 1: The Flightless Wonder

Recent fossil discoveries have unveiled an astonishing tale of resilience in the animal kingdom: an extinct species of flightless bird has managed to make a comeback by re-colonizing its original island habitat and evolving back into existence not just once, but twice in under 20,000 years. This remarkable phenomenon is attributed to a process called 'iterative evolution.'

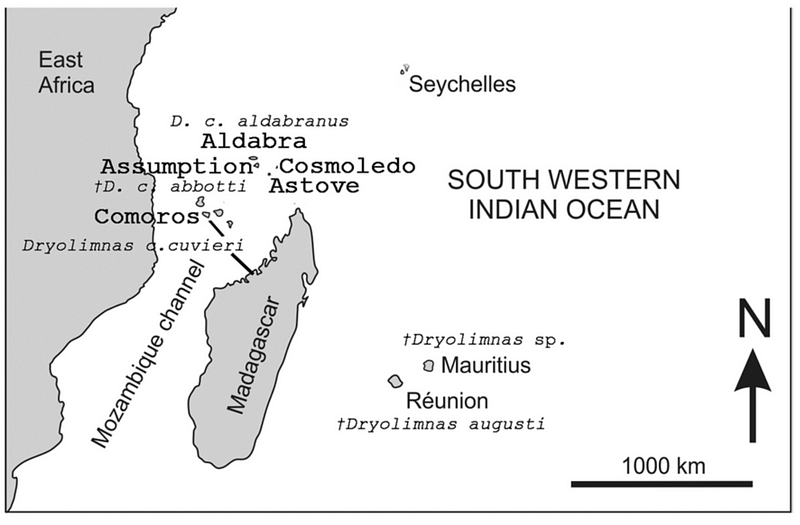

The white-throated rail (Dryolimnas cuvieri), commonly referred to as Cuvier’s rail, is part of the Rallidae family and inhabits regions in the Comoros, Madagascar, Mayotte, and the Seychelles. The bird was photographed in Bemanevika, a protected area in northern Madagascar teeming with endangered wildlife.

Fossil evidence indicates that this bird species once colonized the tiny Aldabra Atoll in the Indian Ocean, where it lost the ability to fly before rising sea levels submerged the island and all its inhabitants around 136,000 years ago.

“Aldabra was completely submerged, and everything vanished,” noted avian paleontologist Julian Hume from the Natural History Museum. “There was almost a total turnover of the fauna, resulting in the extinction of various endemic species, including a crocodile, a duck, a tortoise, and the rail itself. Nevertheless, the Aldabra rail persists today, indicating a remarkable story of survival.”

The Ice Age played a pivotal role, as falling sea levels allowed Aldabra to resurface approximately 118,000 years ago. Consequently, the white-throated rail returned to the island, once again losing its flight capability, leading to the flightless bird we recognize today.

The Aldabra rail (Dryolimnas cuvieri aldabranus) is a striking bird roughly the size of a chicken, standing as the last flightless bird in the Indian Ocean. It shares a close lineage with the white-throated rail, which, unlike its Aldabran cousin, retains the ability to fly.

“The flightless Aldabra rail is nearly indistinguishable in color and shape from its ancestor, the white-throated rail of Madagascar,” Dr. Hume explained. However, the two species can be differentiated easily because the white-throated rail can still take to the skies.

So, what prompted the ancestral white-throated rails to leave Madagascar initially?

“Something triggers them, causing them to disperse in all directions,” Dr. Hume stated. “This may occur every fifty to a hundred years. While the exact mechanism remains unclear, some of the birds manage to land on islands.”

Frequent population surges of white-throated rails in Madagascar might drive flocks to venture out and repeatedly colonize isolated islands across the Indian Ocean. However, most of these adventurous birds do not survive: those that flew north or south often drowned at sea, while those heading west faced terrestrial predators in Africa. Conversely, some fortunate individuals made it to remote islands like Mauritius or Réunion, which were home to other flightless birds like the dodo (Raphus cucullatus) and the sacred ibis of Réunion (Threskiornis solitarius). Occasionally, some managed to reach the small Aldabra atoll safely.

Aldabra is unique, having formed around 400,000 years ago, and boasts the oldest paleontological record among oceanic islands in the Indian Ocean. Throughout its history, it has faced inundation several times due to rising sea levels, making its fossil evidence a clear testament to the impact of environmental changes on extinction and recolonization events.

Dr. Hume's research involved collaboration with David Martill, a paleobiologist specializing in pterosaurs and theropod dinosaurs at the University of Portsmouth. The pair meticulously measured and compared fossils from periods before and after the inundation events.

Their studies revealed that the fossilized wing bones of the ancient Aldabra rails were smaller than those of the ancestral white-throated rail, indicating a significant shift towards flightlessness. Moreover, the lower leg bone fossils were more robust, suggesting that the Aldabra bird was growing heavier, further losing its ability to fly.

Remarkably, these two flightless bird species on Aldabra evolved from the same ancestor within a mere 16,000 years, marking one of the swiftest rates of flightlessness evolution documented in avian history through iterative evolution.

Iterative evolution describes the recurring emergence of similar anatomical features from the same ancestor at different times. This phenomenon is evident in various fossil records, including ammonites and the dugong, which underwent iterative evolution over the last 26 million years.

Dr. Hume remarked, “These remarkable fossils provide undeniable proof that a member of the rail family colonized Aldabra, likely from Madagascar, and achieved flightlessness independently on multiple occasions. This fossil evidence is unparalleled for rails and exemplifies their ability to successfully colonize isolated islands and evolve flightlessness repeatedly.”

This phenomenon marks the first documented case of iterative evolution in rails and stands as one of the most distinct examples of such evolution in birds to date.

“There is no other instance I can find where the same bird species has undergone flightlessness twice,” Dr. Hume elaborated. “This was not the result of different species colonizing and becoming flightless; it was the exact same ancestral bird.”

Iterative evolution reflects a form of evolutionary conservatism, likely driven by the significant regulatory control of certain genes.

But how do rails lose their flight ability so rapidly?

“In juvenile rails, the wings and flight muscles are the last to develop, rendering the birds flightless until they nearly reach maturity,” Dr. Hume noted. “If they land on a predator-free island, they can evolve flightlessness astonishingly quickly, even in just a few thousand years.”

This rapid evolution of flightlessness arises from the fact that developing and maintaining large wing muscles requires energy that could be redirected toward other vital functions, such as reproduction.

Before human presence disrupted the ecosystems of the Indian Ocean islands, these areas were home to numerous flightless birds, the most famous being the dodo, a large flightless pigeon native to Mauritius. Unfortunately, the arrival of humans and their numerous invasive species, including rats, cats, and goats, led to the extinction of these unique birds. However, the Aldabra rail has managed to survive much of this upheaval.

“Surprisingly, Aldabra rails coexist with rats, even preying on them, but they cannot thrive alongside feral cats. The rails have vanished from Aldabra regions where cats have become feral,” Dr. Hume observed.

Regrettably, with rising sea levels driven by unchecked climate change, the future appears bleak for the Aldabra rails.

“Sadly, this bird is likely to face extinction for the third time,” Dr. Hume lamented. “Aldabra is a low-lying atoll and will disappear if current global warming trends continue unchecked. This will only add to the extensive list of extinctions caused by human activities, rather than occurring naturally.”

Source:

Julian P Hume and David Martill (2019). Repeated evolution of flightlessness in Dryolimnas rails (Aves: Rallidae) after extinction and recolonization on Aldabra, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlz018 | doi: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz018

Originally published at Forbes on 28 May 2019.

Chapter 2: A Journey Through Time

The first video titled "Louis Zamperini's Letter to the Bird" chronicles an emotional narrative connecting humanity and nature.

The second video, "THIS BIRD CRASHED INTO MY WINDOW AND THEN...(MEET ERNIE!)" presents a heartwarming encounter with a bird and its unexpected journey.