# Odysseus and the Cynics: A Philosophical Exploration

Written on

Chapter 1: The Hero Through a Philosophical Lens

The character of Odysseus, known as Ulysses to the Romans, has captivated audiences for generations. I vividly recall watching a 1968 miniseries on Rai, which brought the Odyssey to life and left a lasting impression on my young mind, particularly the chilling figure of Polyphemus the Cyclops. The performances of Bekim Fehmiu as Odysseus and Irene Papas as Penelope remain etched in my memory as the definitive portrayals of these iconic characters.

Odysseus, particularly in the context of the Odyssey (as opposed to the more complex character in the Iliad), has served as a source of inspiration throughout my life. His intellect, bravery, and selflessness—evident in his choice to forsake immortality for the sake of returning to his family—have been guiding principles for me for many years. I have explored the Odyssey in various translations, including a remarkable rendition by Robert Fagles, which comes with an insightful introduction by Bernard Knox.

The Stoics believed that having role models is essential for personal growth, as they provide templates for virtuous behavior. While it is possible to articulate the essence of virtue, the most effective way to embody it is to study the lives of exemplary figures. Traditional Stoic role models include Socrates, Cato the Younger, and Hercules, but I intend to delve into the character of Odysseus through the lens of Silvia Montiglio's intriguing work, From Villain to Hero: Odysseus in Ancient Thought. This will allow me to revisit my childhood hero while exploring various philosophical perspectives.

Montiglio's book offers a profound examination of how Odysseus has been perceived by different philosophical schools. In this essay, I will focus on Odysseus and the Cynics, while future posts will discuss his representation by the Stoics and Epicureans, providing a broad overview of Odysseus' character and the philosophical traditions surrounding him. Additionally, I will include a fourth essay on Dante’s portrayal of Odysseus, based on Gabriel Pihas' paper titled “Dante’s Ulysses: Stoic and Scholastic models of the literary reader’s curiosity and Inferno 26.”

Tell me, Muse, of the man of many adventures. (Odyssey, 1.1)

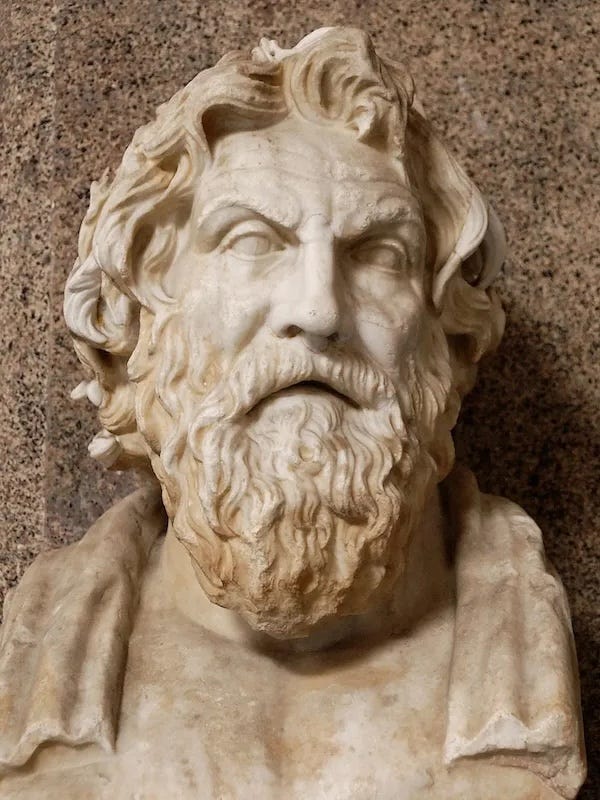

Let’s start with the Cynics, particularly Antisthenes’ interpretation of Odysseus. A disciple of Socrates, Antisthenes initially studied rhetoric under Gorgias, eventually adopting an ascetic lifestyle and establishing the Cynic school, although Diogenes of Sinope is often viewed as its most famous representative.

Montiglio notes that Antisthenes was the first philosopher to offer a systematic defense of Odysseus’ character, countering critiques regarding his alleged disrespect toward Poseidon during the Cyclops episode. He commends Odysseus for rejecting Calypso’s offer of eternal life and defends his adaptability and resourcefulness as a leader in both warfare and everyday challenges. (Montiglio, p. 20).

Antisthenes argues against the negative portrayals of Odysseus by Greek tragedians, who criticized his persuasive abilities, labeling him as deceptive. He asserts that Odysseus is not a Sophist; rather, his capacity to articulate thoughts from various angles highlights his wisdom:

"Finding the right way to express wisdom for each situation is a sign of intelligence, while failing to adapt speech for different audiences reveals ignorance." (p. 22).

Unlike Socrates, who professed ignorance, Antisthenes believed that Odysseus possessed knowledge. Thus, his persuasive skills are portrayed as a means to guide others towards truth and benefit:

"Odysseus speaks virtuously, not with the intent to deceive, but to help others uncover what is true and advantageous for them." (p. 23).

The distinction between the wise Odysseus and a manipulative Sophist lies in their motivations: where the Sophist seeks to control, Odysseus aims to encourage virtue.

Antisthenes also defends Odysseus in a famous scene from the Iliad where Ajax and Odysseus vie for Achilles’ armor. Ajax presents himself as the archetypal warrior, noble and fierce, while Odysseus highlights his willingness to humble himself for the greater good, demonstrating his commitment and cleverness.

Antisthenes even adopts a Socratic style in Odysseus’ argument, emphasizing intellect over brute strength. Odysseus challenges Ajax, saying: "You, who don't understand how to fight, are driven by anger like a wild boar." (p. 26).

Historical figures like Themistocles and Pericles have recognized Odysseus' cunning, with Themistocles earning the moniker "Odysseus" for his strategic acumen. Pericles famously commended the Athenian populace for balancing courage with prudence, unlike their more reckless counterparts.

Returning to the Ajax episode, Odysseus’ critique of Ajax's ignorance resonates with Socratic undertones: "I do not hold your ignorance against you; it is a burden you bear unwillingly." (p. 28). This assertion challenges Ajax's capabilities, suggesting that his traditional warrior ethos, reliant solely on physical might, proved ineffective against the Trojans over a decade.

Odysseus fits the Cynic mold, as he willingly dons rags for a specific mission, embodying the Cynics' minimalist philosophy. He disregards superficial appearances and, like the Cynic who acts for the benefit of others, he undertakes his quests for the public good, often in solitude. (p. 29).

The contrast with Ajax is stark: "Odysseus has no qualms about acting in ways that others would find dishonorable, while Ajax would never dare to do so." Odysseus cleverly counters Ajax: "If others were to witness my actions, I would not be bold for the sake of reputation." Montiglio aptly states: "In the competitive realm of the Iliad, Odysseus emerges as the most cooperative hero, most concerned with the common good and least fixated on honor." (pp. 31–32).

Antisthenes admired Odysseus’ knack for escaping dire situations through wit, exemplified in the Cyclops episode, where he blinds Polyphemus and cleverly escapes by hiding among sheep. When questioned about his identity, Odysseus cleverly claims to be "Nobody," ensuring that when other Cyclopes come to help, they are told that "nobody" harmed him.

Yet, Odysseus embodies more than just cleverness; he also epitomizes virtue. Antisthenes equates his choice to leave Calypso and endure hardship in order to return home to Hercules' similar decision to prioritize virtue over pleasure.

Antisthenes authored two works on Hercules, though only their titles survive: The Greater Heracles or On Strength and Heracles or On Wisdom. He was selective in emphasizing certain aspects, seemingly overlooking Hercules' well-known appetites. Moreover, the hardships Hercules endured were reinterpreted by the Cynics (and Stoics) as a matter of personal choice, rather than fate.

Such mythological role models serve a purpose; they provide a lens through which we can examine the essence of virtue and heroism.

Next, we will explore Odysseus through the Stoic perspective.

Chapter 2: Insights from the Stoics

In this video, "A Long and Difficult Journey, or The Odyssey: Crash Course Literature 201," we explore the nuances of Odysseus' character and his literary significance.

Chapter 3: The Cynics' Perspective

In "The Cynic School of Philosophy | How To Study: Sadler's Advice," we delve into the principles of Cynicism and how they relate to figures like Odysseus.