# Neanderthals: Pioneers of the First Known "Museum Collection"

Written on

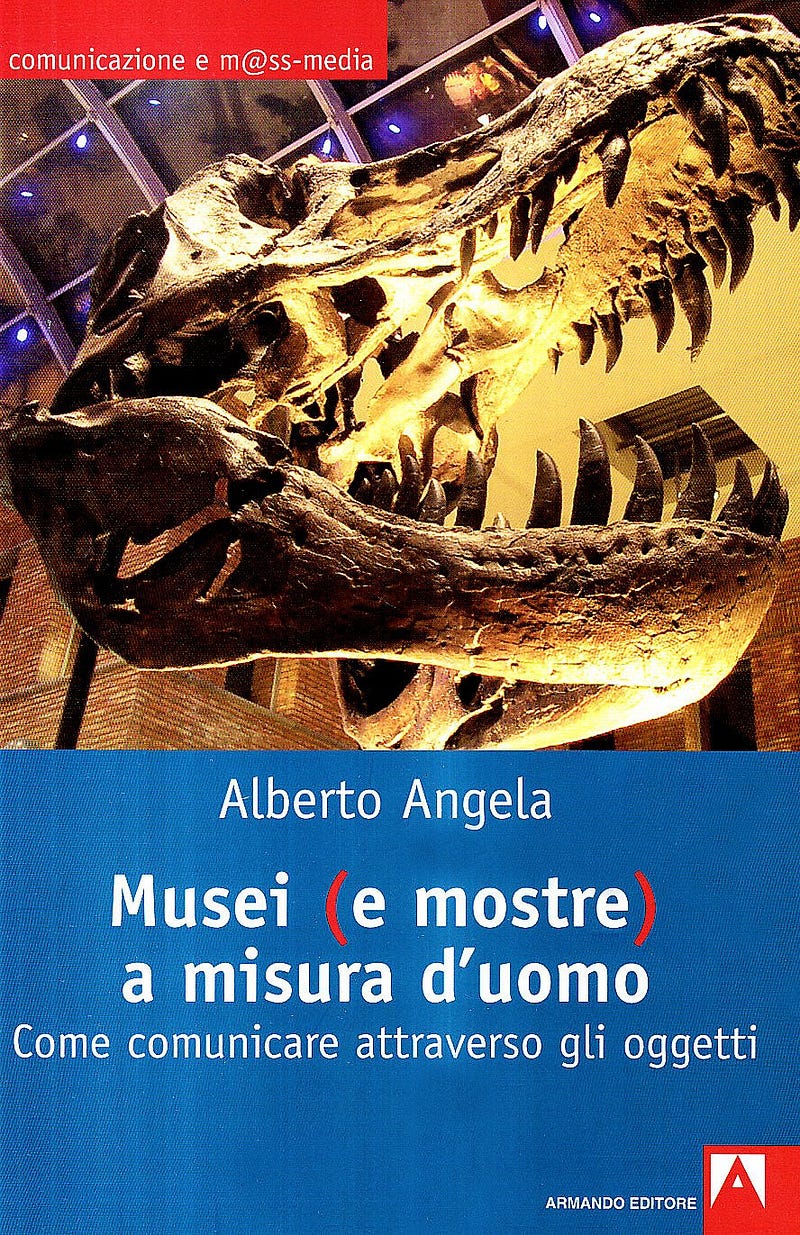

Chapter 1: The Origins of Artifact Collection

In a classic science text from the late 1980s by Italian science communicator Alberto Angela, it was noted that a cave inhabited by Neanderthal hunters contained an intriguing arrangement of items: a large quartz crystal, a marine gastropod shell, and a piece of deer antler. The purpose of this eclectic collection remains unclear. These artifacts could have held magical significance, but if they weren't simply placed there at random, they might represent the earliest naturalistic collection discovered to date, possibly serving as a precursor to today's Natural History Museums.

This book, written over three decades ago, is hard to locate, but it raises fascinating questions about the collecting behavior of Neanderthals. For instance, in the Cuevas Des-Cubierta cave in Spain's Madrid region, researchers unearthed skulls of various ancient herbivores, dated to approximately 40,000 years ago, alongside bones, tools, and the remains of a young Neanderthal child aged between three and five. As a paleoanthropologist, I rely heavily on museums for my research, which play a crucial role in advancing scientific knowledge. Let's explore the history of these remarkable institutions that have been instrumental in scientific exploration for centuries.

Chapter 2: The Evolution of Museums

The inaugural Natural History Museum, established in 1568 in Bologna, Italy, by naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi, aimed to gather natural and historical wonders from around the globe. However, the practice of collecting artifacts predates this institution. Even the Romans recognized the historical value of Etruscan artifacts, creating early forms of museums or personal collections that functioned similarly.

With Neanderthals, this behavior can be traced back tens of thousands of years. At a site, researchers found bones scattered across the floor, with large skulls—more than just crania—meticulously extracted from their original bodies, suggesting they were modified using fire or tools. The remains included 35 skulls from 28 bovid species (like aurochs and bison), five cervids, and two rhinoceroses, indicating deliberate placement. These skulls likely served as "mementos," supported by the absence of mandibles and teeth and evidence of processing marks.

It seems probable that Neanderthals removed the skulls outside the cave after processing the carcasses and later used the cave for removing the brain.

Chapter 3: Cultural Significance of Neanderthal Collections

The rarity of preserving only skulls among hunter-gatherer societies—both ancient and contemporary—is noteworthy, as they are not typically considered "nutritious." The lack of meat, the accumulation of remains over a brief period, and the excellent preservation of horns imply that this could be a form of a "trophy room" or have served some ritualistic purpose.

While the exact meaning of this collection remains speculative, it clearly reflects a symbolic connection that Neanderthals had with the natural world. The presence of various tools showing signs of percussion and cutting suggests that the intentional gathering of these bones was a cultural practice transmitted across generations. Additional scientific evidence supports this notion.

Moreover, this discovery challenges the belief that anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) were the first to collect modified skulls.

Chapter 4: Understanding Neanderthal Behavior

From a personal standpoint, these findings are intriguing as they illuminate the "personality" of the Neanderthals. Each discovery helps us appreciate how closely related the Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were—not just in physical traits but in their interactions with nature. We now recognize that we share a mutual admiration for the natural world and a passion for its preservation, revealing that perhaps we were not so different after all.

Published in Fossils et al. Follow to learn more about Paleontology and Evolution.