The Complexities of Race in Genetics and Culture: A Deep Dive

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Race and Genetics

In the film GATTACA, the narrative centers on genetic engineering and its implications. This theme resonates with the ongoing conversation about what the human genome reveals regarding race and genetics.

At a recent NCAA Division 1 hockey match, I overheard a mother urging her son, who had fallen on the ice, to "shake it off and get back up!" As he complied, she proudly remarked, “That’s the German in him!” This kind of sentiment reflects a common pride in heritage, albeit often overlooking negative stereotypes. If he had remained down, it’s unlikely she would have celebrated his Teutonic roots.

While this family identified strongly with American culture, their ancestry likely traced back to Germany. The mother's comment, while perhaps lighthearted, hinted at a deeper belief in the influence of biological heritage or cultural norms. Does German heritage contribute to the hockey player's resilience? This seems a significant leap.

The underlying message was about genetics; she probably associated their shared ancestry with a specific trait—namely, that Germans are tough—suggesting a genetic basis for this quality.

What does this inclination to categorize ourselves reveal about our understanding of race?

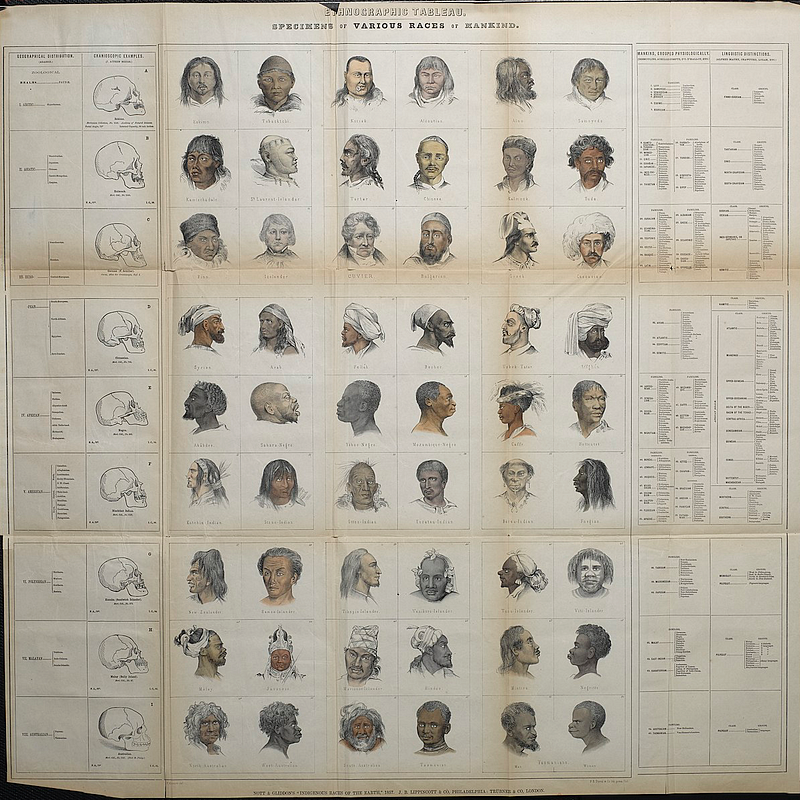

Section 1.1: The Concept of Race

Race is fundamentally a social construct lacking scientific validity. Although it partially arises from physical similarities among groups, it carries no intrinsic biological significance.

According to Wikipedia, referencing various scholarly works, "Taking race out of human genetics" emphasizes this notion. Humans possess around 46,000 genes, with only about 20,000 influencing protein production. The vast array of traits governed by our genes is staggering, yet only a minuscule fraction dictates prominent physical traits commonly associated with race.

How, then, can we justify the concept of race when the genetic basis is so limited?

Subsection 1.1.1: The Illusion of Racial Categories

Scientists assess children's cognitive growth through various tests, such as "conservation of fluid." In one experiment, a child observes liquid being transferred from a short, wide container to a tall, thin one. Initially, they may believe the taller container holds more, reflecting a misunderstanding of fundamental properties based on superficial appearances.

Much like this child, society tends to assign racial categories based on surface-level physical traits, overlooking the deeper genetic similarities that unite humanity.

Section 1.2: Genetics and Heredity

Genetics is the study of heredity, with DNA containing our genes. Each gene consists of base pairs, structured in the well-known double helix. The four bases in DNA—adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T)—combine to form these pairs.

Humans have approximately three billion base pairs organized into 23 chromosomes. Despite the commonalities, only a fraction of our genetic code is responsible for visible traits, such as height or skin color.

In 1972, Richard Lewontin discovered that only 6.3% of the human genome could be attributed to race. While some challenge the validity of his findings, a consensus exists that race does not serve as a meaningful framework for understanding human DNA.

Chapter 2: The Role of Heritability in Race

In the context of genetics, heritability measures the extent to which genetics influences observable traits. Despite the known contributions of environment, heritability can vary significantly across traits.

For example, while height may be 60-80% heritable, environmental factors, such as nutrition, play a crucial role. Conversely, certain genetic conditions, like Phenylketonuria (PKU), are entirely hereditary.

Thus, even when genetic factors align with specific racial categories, environmental influences can significantly alter expressions of those traits.

The perception of race persists largely because society believes in its significance. This belief is perpetuated through generations, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy where race continues to shape our interactions and perceptions.

The concept of race survives through a network effect; as more individuals accept race as a defining characteristic, others follow suit, further entrenching its societal relevance.

Will the idea of race eventually diminish?

The persistence of race is reinforced by historical discrimination, as society strives to rectify these injustices. This often leads to the collection of demographic data based on race, which can inadvertently sustain the concept.

Despite the pain caused by the notion of race, many individuals take pride in their heritage. Black Americans, for instance, have cultivated a strong sense of identity and pride, as exemplified by Nina Simone's anthem, "To Be Young, Gifted and Black."

The complexity surrounding race demonstrates that while it is a construct, it is not easily dismissed.

Thanks to Patricia Jeanne and Susan Brearley for their editorial contributions.