A Historical Perspective on American Policing: From Property to People

Written on

Chapter 1: The Origins of American Policing

Across the United States, many people share a common misunderstanding about the role of law enforcement, believing it is fundamentally “to protect and serve.” This assumption is often thought to be enshrined in law or the Constitution, yet the truth is far more complex and recent.

In 1955, the Los Angeles Police Department initiated an internal contest to find a new motto for their growing Police Academy. Officer Joseph S. Dorobek proposed the phrase “To protect and to serve,” which gradually came to symbolize the entire department. By 1963, the Los Angeles City Council had officially adopted it, placing it alongside the city seal on patrol vehicles.¹

The widespread confusion regarding this motto likely stems from numerous films and television shows set in Southern California that feature the LAPD. However, the actual history of police departments in America tells a much darker and more complicated story. Professional policing emerged not from a desire to safeguard the public from crime but rather to protect the interests and property of the affluent from a potentially unruly populace.

Chapter 2: Slave Patrols and Property Protection

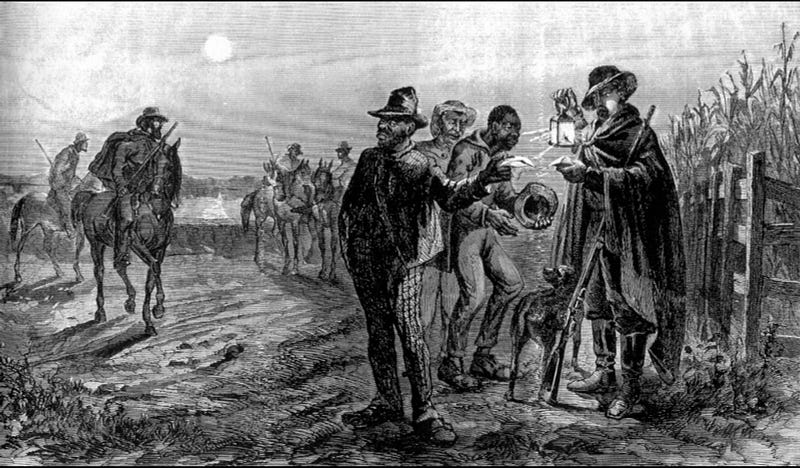

In the early 1700s, wealthy Southern plantation owners created informal militia units known as “Slave Patrols” to intimidate and suppress potential slave revolts and to recapture runaways. Their primary goal was to instill fear among those who might resist, employing harsh and public punishments to maintain control.²

The stark divide between the affluent and the impoverished during this time was significant; one percent of the population possessed nearly 45% of the wealth. Indentured servants were frequently treated as commodities, with the British Parliament endorsing the transportation of criminals to the New World as a legitimate punishment.

Wealthy landowners, perpetually anxious about uprisings, often hired mercenaries to safeguard their assets. To prevent a united front among marginalized groups, concerted efforts were made to keep Indigenous peoples, enslaved individuals, and impoverished whites segregated.³

Historian Howard Zinn notes, “More than half the colonists who came to the North American shores in the colonial period came as servants.” While the number of indentured servants dwindled as they sought freedom or completed their terms, as late as 1755, they still constituted 10% of Maryland’s population.³

The first organized armed groups, therefore, were fundamentally established to protect the property rights of the wealthy elite.

Chapter 3: The Jim Crow Era and Systemic Oppression

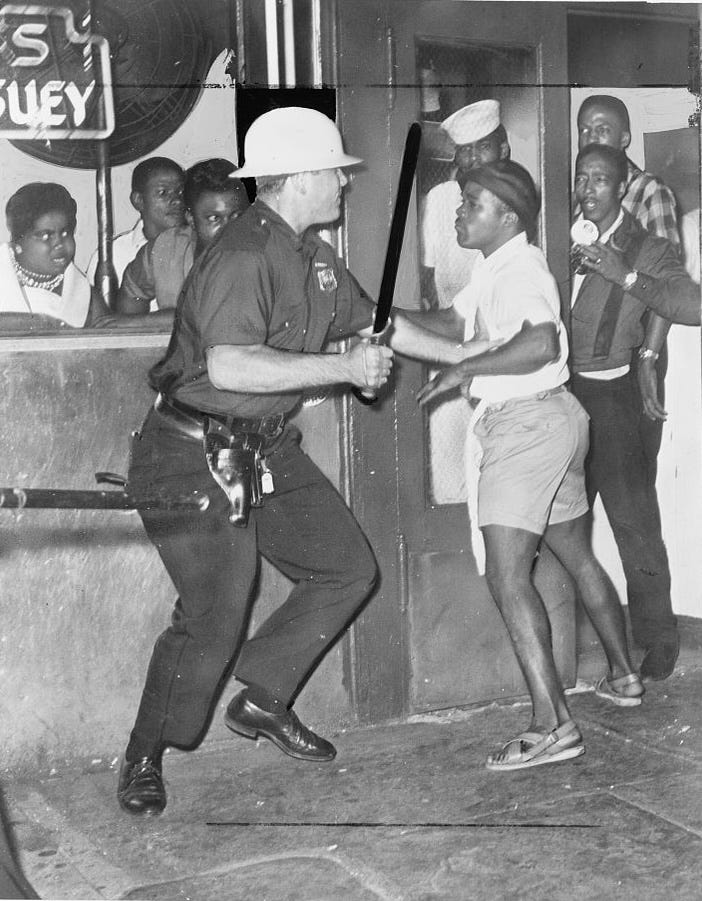

Following the Civil War, Southern laws known as Black Codes were enacted to maintain a supply of inexpensive or unpaid labor by limiting the rights of Black Americans. Although the 14th and 15th Amendments were supposed to abolish these codes, Southern states soon implemented Jim Crow laws, which continued to restrict Black Americans' economic opportunities and civil rights.

Real progress for Black Americans would not begin until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, during this period, groups like the Ku Klux Klan terrorized Black communities while police often turned a blind eye, or even participated in the oppression.

Chapter 4: Establishing Professional Police Forces

For much of colonial America, there was no formal law enforcement system; instead, there were privately paid night watchmen who walked the streets to prevent disturbances. Sometimes, vigilante groups formed to enact justice against bandits and cattle rustlers.

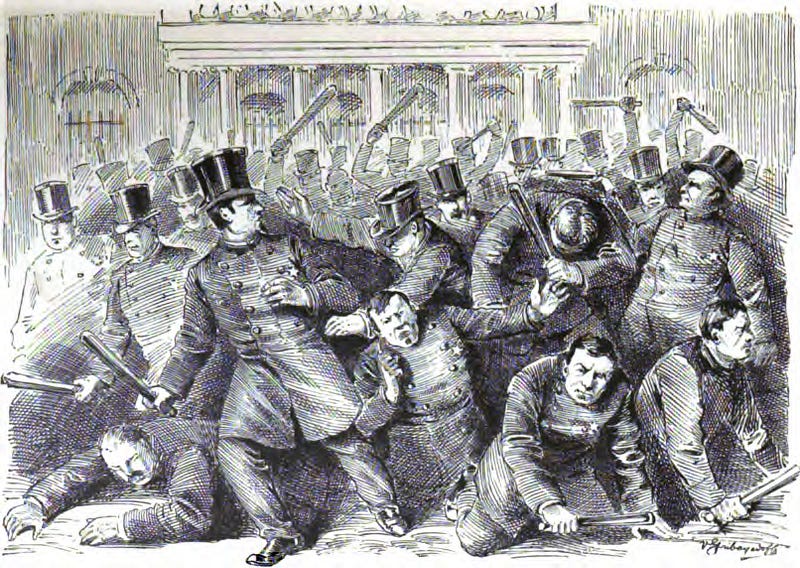

The early 19th century saw a significant influx of German and Irish immigrants into American cities, which heightened tensions among existing populations. In response to rising unrest, the first professional police department was founded in New York City in 1845, soon followed by other cities. Initially, these departments lacked investigative functions and were primarily focused on maintaining order among various ethnic groups while protecting the interests of the wealthy.

The evolution of policing in America can be divided into four distinct eras: the Political Era (1840–1890), the Reform Era (1900–1950), the Community Era (1980–2000), and the Homeland Security Era (2001–Present).

The Political Era was characterized by police departments being managed by politicians, often serving the interests of the affluent. This led to widespread corruption and brutality, paving the way for the Reform Era.

August Vollmer, who served as Chief of Police in Berkeley, California, from 1905 to 1932, implemented reforms that laid the groundwork for modern policing. He established the first police academy, emphasizing the need for officers to be trained and tested for psychological and intellectual capabilities essential for effective policing.

However, the social upheaval of the 1960s and the war on drugs in the 1970s shifted the focus back to aggressive policing in impoverished neighborhoods, resulting in a surge of arrests and incarcerations.

Chapter 5: Modern Policing and the War on Drugs

Amidst the challenges of the post-9/11 era, law enforcement sought community support, initiating a phase of community policing aimed at involving citizens in crime prevention efforts. New recruits often came from educational backgrounds, diverging from traditional policing methods.

In 1974, the Kansas City Preventive Patrol Experiment aimed to determine the effect of increased police patrols on crime rates, concluding that such measures had little impact. Subsequent studies reinforced this notion, suggesting that aggressive policing often led to negative outcomes in marginalized communities.

The militarization of police began in the 1960s, driven by civil unrest and anti-war demonstrations. This trend accelerated in the 1980s with the military's increasing involvement in domestic law enforcement, culminating in the 1997 North Hollywood shootout that radically transformed policing across the nation.

Since then, numerous police departments have participated in the 1033 Program, which facilitates the transfer of military surplus equipment to local law enforcement. This has resulted in the widespread availability of military-grade weapons and gear, fostering a culture that prioritizes militaristic approaches to community safety.

The first video, "Ep. #316: Do police have a duty to protect?" explores the legal and ethical obligations of police in safeguarding communities, raising critical questions about their role in society.

The second video, "Cop Enters Private Property Without Consent - Forces Man To Give His Name!" showcases an alarming incident reflecting the complexities of policing and individual rights.

Chapter 6: The Ongoing Struggle for Justice

Recent years have seen a surge in high-profile cases of extrajudicial killings by police, igniting national outrage and calls for reform. The tragic deaths of individuals such as George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Tyre Nichols have underscored the urgent need for accountability within law enforcement.

Despite movements advocating for change, such as Black Lives Matter, the systemic issues within policing remain entrenched, as the culture often perpetuates dehumanization and bias.

As we consider the future of policing in America, it is crucial to reevaluate our approach. We must explore alternatives that prioritize community safety, mental health, and social justice over punitive measures. This shift can pave the way for a more equitable and just society.